Ports/Terminals:

HOQUIAM OIL TERMINAL

Kyle Linden

The proposed Hoquiam Oil Terminal has been a hotly debated issue in Grays Harbor and coastal Washington State. The debates pits the need foremployment against potential dire consequences for fisheries, tourism and other local businesses. Without alternative employment opportunities it will be difficult for residents to keep future fossil fuel companies from moving in. Hoquiam has been suggested as an ideal location to ship fossil fuels from the Bakken Oil Shale Basin and Alberta Tar Sands, by means of supertankers. These products would then be refined before being shipped to oil-thirsty markets in Asia.

Fishing for a Living

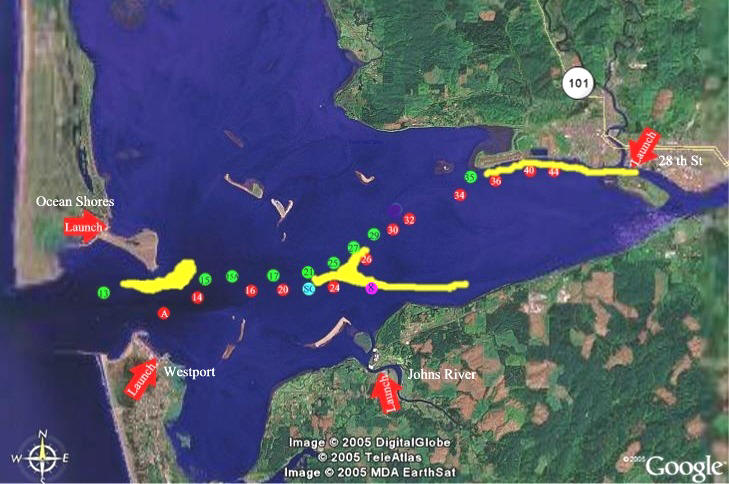

Common local fisheries fishing areas in yellow (Credit: DigitalGlobe)

Among the greatest concerns for oil export terminals are from those who make their living on the water. The terminals would receive approximately 300 oil tankers per year (Ahearn). The 1989 Exxon Valdez spill in Prince William Sound, Alaska, is still in the back of the fishermen’s minds and the fishing industry in Grays Harbor will be increasingly outspoken. The opposition has included not only the residents of Hoquiam and Aberdeen but has included the Quinault Indian Nation which have treaty rights to harvest fish and shellfish in Grays Harbor and the Chehalis River. (See Quinault & Oil). If a spill were to occur in the harbor or off the coast the fisheries industry, upon which 31% of the local economy depends, would grind to a halt. The vice president of the Washington Dungeness Fishermen's Association, Larry Thevik, said that “any oil that spilled within Grays Harbor or in transit will end up on our shorelines and it will directly impact the crab fishery” (Ahearn). Any damage done to marketable fish, crab, or shellfish would devastate the industry, and increase unemployment. The fisheries could greatly lose stock that would take a long time to bounce back, in particular the lucrative Dungeness crab and shellfish markets that likely would not be replenished in our lifetime.

(Credit: Sightline Institute)

A Need for Jobs

With unemployment as high as 8% in the busier summer months and even higher in slower winter months, Grays Harbor County is struggling to create employment opportunities. 25% of the local economy depends on tourism and recreation, based on the region’s rich natural wonders (Place). A spill would cause tourism and recreation to diminish significantly until the spill was cleaned up, and past clean-ups have proven to be a nearly impossible task. Furthermore, the main shopping centers for Aberdeen and Hoquiam would be blocked for possibly about an hour by each train visiting the terminal area, a projected two trains a day, each one roughly 1.5 miles long. These shopping centers are a key part of the remaining economy and one of the few reasons for visitors to stop in town on their way through. If traffic were stopped for such extended periods of time it would act as a major barrier for residents, as well as a significant deterrent to the very tourists that these communities are hoping to attract.

Allowing these terminals to receive oil trains would effectively cut off the head of the area’s needed tourism. The Westway and Imperium facilities would have offered offer only 45 direct jobs and approximately 100 indirect jobs for the proposed terminals, far short of what the community needs. Yet thousands of local jobs could be impacted if a spill or other incident were to occur, and as one resident stated at a terminal proposal hearing “it’s not if, but when.” About 164,000 barrels are projected to be fed into the refineries daily. Sightline Institute predicted that if an oil spill were to occur within Grays Harbor an estimated 194 jobs would be lost as a direct result, $25 million lost in personal income, and $56 million lost in business revenue. A spill along the Pacific Coast would result in 229 jobs lost as direct result, $28 million lost in personal income, and $70 million lost in business revenue.

Safety Concerns

The Westway and Imperium terminals would be serviced by an estimated two trains per day. There has been growing concern about the safety of these trains in light of the derailed train carrying Bakken Oil that exploded in Quebec in 2013, killing 47 people and wounding many others (See Oil Train Explosions). The very route these trains would be traveling through is the busiest and most frequently visited part of town, along obsolete railways that would take millions of dollars to repair. The possibility of a malfunction or explosion like that in Quebec is a major concern for residents. Trains would serve as a rolling barrier through the town, raising concerns about emergency fire, medical, and spill response times. Senator Patty Murray commented, “We need to have the right policies in place to prevent accidents and respond to emergencies when they do happen” (Song).

Not only is the public at risk, but the fragile ecology of the area is threatened as well. The 1,500-acre Grays Harbor Wildlife Refuge sees 500,000 shorebirds annually and it is next door to the proposed oil terminals. The natural salt marshes of the area store and capture more carbon per acre than boreal forest, rainforests, and mangrove swamps but they are vulnerable to a toxic oil spill. Grays Harbor is ill-equipped to handle such a devastating potential spill and response time would be far less rapid than elsewhere in the country.

Large-scale spills, such as the Exxon Valdez and the BP oil spills, are what come to mind when someone brings up the subject of oil spills. But small-scale spills such as accidental bilge discharges and overfilling fuel tanks are much more common. In the Puget Sound, 757 confirmed spills with a calculated 5,115 gallons of oil occurred in a 38-month span between December 2009 and January 2013, or about 20 per month (De Place). There are already 275 oil pollution incidents in a typical year in the Coast Guard sector along Grays Harbor and the Columbia and Snake Rivers. Though these rarely get much media attention, they have accumulative effects on the waterways and the region’s ecology. If these terminals were to begin operating then these incidents will increase no matter what safety regulations are in effect.

According to the Sightline Institute:

"More ships navigating Puget Sound and the Columbia River and Grays Harbor will mean more oil spills ... that’s not speculation; it’s the conclusion of detailed analysis found in the 2010 Vessel Traffic Risk Assessment (VTRA), a report commissioned by the Puget Sound Partnership to gauge potential oil spill risks associated with proposed terminal projects in northern Puget Sound” (De Place).

Logistical Challenges

Aside from shipping frequent train traffic, another concern over the proposed fossil fuel shipments is the logistical challenge of shipping through the relatively small and dangerous sandbar-infested entrance to Grays Harbor. With a dramatic increase in shipping traffic, the risk of a collision and oil spills will greatly increase. Oil tanker traffic would increase by 44 times, thought to be roughly between 293 and 428 tankers and tug barges carrying oil annually through the fairly shallow and narrow 12-mile long shipping channel of Grays Harbor (Powell). With the current layout of the harbor, there is inadequate deep water staging areas within for large vessels meaning most ships would have to inefficiently wait outside the harbor until the last tanker is full and clear of the harbor entrance. As an environmental group notes, “such a huge surge in oil vessel traffic, in a place not suited to them is inviting disaster” (Stand Up to Oil).

The jetties of Ocean Shores and Westport are also major risks. Several times through history, vessels have met difficult winter weather just outside the harbor, some stalling or losing cargo while drifting toward the rock barriers. In 1988 the tugboat Ocean Services pulling the barge Nestucca carrying 70,000 barrels of bunker fuel attempted to cross the bar into Grays Harbor as a winter storm approached, and the tugboat’s crew attempted to adjust the line, causing it to snap. As the barge drifted closer to the harbor jetty, the crew was able to reestablish the line but not before the two vessels collided, tearing a hole in the barge’s hull. Heavy fuel oil leaked from the damage for 23 hours until weather permitted them to patch it. An estimated 231,000 gallons spilled into the sea, fouling beaches from Oregon to Vancouver Island. For these vessels that make contact with the jetties a spill is almost inevitable (See Oil Tanker Spills).

Hope for the Future

At City of Hoquiam and Centralia hearings on April 25 2014, over a hundred local residents gathered to voice their concerns. A vast majority voiced their opposition to the proposed oil terminals and made it clear that the oil industry is not where they should be looking for future employment solutions. By April 2016, two of the oil terminals had been dropped by U.S. Development Group and REG, leaving only the Westway proposal still on the table (Schild).

Over 100 people gathered at local Hoquiam high school with questions and concerns about proposals to build train-to-ship oil terminals in their community on April 2014 (Credit: Oregon Public Broadcast, Ashley Ahearn)

“It’s a step in the right direction. The cons of the whole idea of bringing petroleum products into this harbor are overwhelming, I was disappointed that there was no mention of the current projects, but still it seems like a real sea change in the way that the mayor and the council are finally coming around to understand that growth at any cost is not good for the city of Hoquiam.”

-Grays Harbor resident, Diane Wolfe, speaking at the Oil Terminal Hearings

Remarks by Arnie Martin, Grays Harbor Audubon Society, at the "Shared Waters, Shared Values" rally at Hoquiam City Hall, July 8, 2016:

"You might now know it, many people don't, but Grays Harbor is world famous in the birding world. It's a hot spot for shorebirds and the falcons that prey on them. Our Grays Harbor National Wildlife Refuge is visited by hundreds of thousands of shorebirds annually, with up to 23 different species arriving during the year. It is a state of hemispheric importance. During the spring migration, the closest major feeding site to the south is San Francisco Bay. The next large area to the north is the Copper River delta in southeast Alaska. That's 1,280 miles away. That's a very long way for a little bird.Some birds traveled from Argentina to their Alaska breeding ground, but most come from Central America. I want everybody to hold your palm out like this. Imagine you have a bird in your hand. You would hardly notice it, but they fly more than 60 miles to get to the food in Grays Harbor. That small shorebird weight less than a slice of bread. The birds need the food, invertebrates and plants on the refuse. The mud flats have up to 50,000 invertebrates per square meter.The spring migration is an exciting tme at the refuge with hundreds of students bused in on nature trips and thousands of visitors coming to see the birds during the month long migration, and to the Shorebird Festival at the peak migration weekend. Our 12.5 hour title cycle means that about two times a day the estuary water leaves and enters the refuse. Most days, the title velocity exceeds one knot four times per day as Larry said, meaning the tanker vessel loading can't be efficiently pre-boomed. Without pre-booming, if there are even small spills, the crude oil will reach the water and the tide will carry it to the refuge during the next title cycle. The response time to report spills does not allow adequate time to boom the refuge, and the booming plan is outdated.Even one drop of oil on a shorebird's feathers harms their insulation value, raising the possibility of hypothermia. It's not very cold in Grays Harbor, but with water temperatures from 40 to 60 degrees, the birds must maintain the body temperature of 105 degrees. Hypothermia acts quickly. Poisoning is even quicker. The birds preening the caustic crude from their feathers corrodes the birds stomach lining, spelling sure death.As Larry mentioned, there are 56,000 birds confirmed killed by the 231,000 gallon spill of heavy oil from the barge of Nestucca in 1989, and, unknown, thousands of seabirds...died silently in the ocean depths. The people of Grays Harbor remember the Nestucca. We don't want another spill. Not ever.Think, what could happen in a worst case scenario if there were nearly a million barrels of oil, that's 42 million gallons, sitting a few hundred feet from the shore of the estuary and there was a major accident? More than a million birds could die a tortured death from such a spill. Can the...barge project guarantee safety? Can they insure us with enough funds to recover from such a calamity? There not enough insurance resources in the entire state for such a recovery.If Bowerman Basin and the estuary are polluted with oil, the birds cannot just find another place to feed. There would be no adequate site for the migration, feeding, and rest stops between San Francisco Bay and Alaska, and that is way too far for tiny birds to fly. We need to protect what we have because it cannot be replaced by order 100,000 to 200,000 bird meals a day from McDonald's. Grays Harbor Audubon Society and other Audubon Washington chapters are part of the Regional Coalition Stand Up to Oil campaign, working to protect communities in Northwest waters ranging from Grays Harbor, Puget Sound, and the Columbia River from the risk of oil train derailments and oil spills from trains, tanks, and barges.President Sharp has told us the Quinault Nation plans for the benefit of the next seven generations. That's roughly 35 to 70 shorebird generations, and we should make all efforts to protect those generations of shorebirds from destruction. If the refuge is polluted by crude oil, it would take decades to bring it back to some semblance of what it is today. If all goes as planned, the 3rd and 4th grade children of the harbor will be given classroom instruction, nature studies, and refuge field trips this coming year. If the refuge is ruined, what will we show them as a good example of our protection of the national wonders which we enjoy today? We would have failed to protect even the first generation, let alone the seventh."Sources

Ahearn, A. (2014, April 25). Residents voice fear and concern over Grays Harbor oil terminals. Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Mittan, K. (2015, March 10). Council votes 9-1 in favor of oil moratorium. The Daily World.

De Place, E. D, & Stroming, A. (2015, January 26). Northwest oil spills: The raw data and the growing risk. The Sightline Institute.

De Place, E. , & Stroming, A. (2015, January 12). Fifty years of oil spills in Washington's waters. The Sightline Institute.

Powell, T., & Place, E. D. (2015, September 17). The impacts of a Grays Harbor oil spill, in 13 slides. The Sightline Institute.

Schild, Jake (2016, April 2). Grays Harbor Rail Terminal opts out of option-to-lease agreement at the Port The Daily World

Song, K. M. (2014, April 9). Sen. Murray seeks safety assurances as state oil-train transport increase. The Seattle Times.

Stand Up to Oil. (n.d.). Oil terminals. Stand Up to Oil.

Vleming, J. (2015, December). Grays Harbor County Profile. Employment Security Department.